Procesadores de Lenguajes

3º. 2º cuatrimestre. Itinerario de Computación. Grado en Ingeniería Informática. ULL

Organization ULL-ESIT-PL-1920 Github Classroom ULL-ESIT-PL-1920 Campus Virtual PL Chat Chat Profesor Casiano

Table of Contents

- Tema 2: Expresiones Regulares y Análisis Léxico

- Expresiones Regulares

- El Constructor

- Test

- exec

- match

- El operador OR: Circuito Corto

- Parenthesis

- The Date Class

- Word and string boundaries

- Backreferences in pattern: \N and \k<name>

- Backtracking en Expresiones Regulares

- Diophantic Equations

- replace

- Using a function to compute the replacement string

- Greed and Lazy Operators

- Positive Lookahead

- Negative Lookahead

- Positive Lookbehind

- Negative Lookbehind

- Ejercicio: Poner Blanco después de Coma

- search

- lastIndex

- Sticky flag “y”, searching at position

- Analizadores Léxicos usando la Sticky flag

- Parsing Ficheros ini

- Ejercicios

- Práctica p3-t2-regexp

- Unicode, UTF-16 and JavaScript

- RegExps en Otros lenguajes

- Análisis Léxico

- Referencias

- Expresiones Regulares

Tema 2: Expresiones Regulares y Análisis Léxico

Expresiones Regulares

El Constructor

The RegExp constructor creates a regular expression object for matching text with a pattern.

Literal and constructor notations are possible:

/pattern/flags;

new RegExp(pattern [, flags]);

- The literal notation provides compilation of the regular expression when the expression is evaluated.

- Use literal notation when the regular expression will remain constant.

- For example, if you use literal notation to construct a regular expression used in a loop, the regular expression won’t be recompiled on each iteration.

- The constructor of the regular expression object, for example,

new RegExp("ab+c"), provides runtime compilation of the regular expression. - Use the constructor function when you know the regular expression pattern will be changing, or you don’t know the pattern and are getting it from another source, such as user input.

- When using the constructor function, the normal string escape rules

(preceding special characters with

\when included in a string) are necessary. For example, the following are equivalent:

var re = /\w+/;

var re = new RegExp("\\w+");

Ejercicio

- Ejercicio: Usar new Regexp(“string”) versus slash literal. Similitudes y diferencias. Vídeo del profesor

- Explique la diferencia observada entre las dos formas de construir una RegExp

Test

exec

- RegExp.prototype.exec

The exec() method executes a search for a match in a specified string. Returns a result array, or null.

If you are executing a match simply to find true or false,

use the RegExp.prototype.test() method or the String.prototype.search() method.

match

El operador OR: Circuito Corto

- ¿Cual es la salida? ¿Porqué?

> "bb".match(/b|bb/)

> "bb".match(/bb|b/)

Parenthesis

¿Que casa con cada paréntesis en esta regexp para los pares nombre-valor?

> x = "h = 4"

> r = /([^=]*)(\s*)=(\s*)(.*)/

> r.exec(x)

>

console.log(/bad(ly)?/.exec("bad"));

// → ["bad", undefined]

console.log(/(\d)+/.exec("123"));

// → ["123", "3"]

The Date Class

function getDate(string) {

let [_, month, day, year] =

/(\d{1,2})-(\d{1,2})-(\d{4})/.exec(string);

return new Date(year, month - 1, day);

}

console.log(getDate("1-30-2003"));

// → Thu Jan 30 2003 00:00:00 GMT+0100 (CET)

Word and string boundaries

> /\d+/.exec('b45a')

[ '45', index: 1, input: 'b45a' ]

> /^\d+$/.exec('b45a')

null

console.log(/cat/.test("concatenate"));

// → true

console.log(/\bcat\b/.test("concatenate"));

// → false

Backreferences in pattern: \N and \k<name>

We can use the contents of capturing groups (...) not only in the result or in the replacement string, but also in the pattern itself.

By Number

A backreference \n inside a regexp, where _n_ is a positive integer. A back reference to the last substring matching the n parenthetical in the regular expression (counting left parentheses).

For example, /apple(,)\sorange\1/ matches 'apple, orange,' in "apple, orange, cherry, peach."

See also section Backreferences in pattern: \N and \k<name> of the book The Modern JavaScript Tutorial

> chuchu = /^(a+)-\1$/

/^(a+)-\1$/

> chuchu.exec("aa-aa")

[ 'aa-aa', 'aa', index: 0, input: 'aa-aa' ]

> chuchu.exec("aa-a")

null

> chuchu.exec("a-a")

[ 'a-a', 'a', index: 0, input: 'a-a' ]

> chuchu.exec("a-ab")

null

Forward References

Forward references can also be used, but be sure the referenced parenthesis

has matched when is going to be used. This usually means that the forward reference

is inside some repetition group. For example, this regexp matches with train only if

it is prefixed by at least one choo:

[~/.../github-actions/225-github-actions-demo(master)]$ node

Welcome to Node.js v13.5.0.

Type ".help" for more information.

> regex = /(\2train|(choo))+/

/(\2train|(choo))+/

> regex.exec('choochootrain')

[

'choochootrain',

'train',

undefined,

index: 0,

input: 'choochootrain',

groups: undefined

]

It works also in other languages as Ruby and Perl:

$ irb

irb(main):052:0> regex = /(\2train|(choo))+/

=> /(\2train|(choo))+/

irb(main):053:0> 'choochootrain' =~ regex

=> 0

irb(main):054:0> $&

=> "choochootrain"

irb(main):055:0> $1

=> "chootrain"

irb(main):056:0> $2

=> "choo"

By Name

To reference a named group we can use \k<name>

[~/javascript-learning/xregexpexample(gh-pages)]$ nvm use v13

Now using node v13.5.0 (npm v6.13.4)

> regexp = /(?<quote>['"])([^'"]*)\k<quote>/;

/(?<quote>['"])([^'"]*)\k<quote>/

> `He said: "She is the one!".`.match(regexp)

[

'"She is the one!"',

'"',

'She is the one!',

index: 9,

input: 'He said: "She is the one!".',

groups: [Object: null prototype] { quote: '"' }

]

Be sure to use a modern version of JS:

[~/javascript-learning/xregexpexample(gh-pages)]$ node --version

v8.1.2

> regexp = /(?<quote>['"])([^'"]*)\k<quote>/;

SyntaxError: Invalid regular expression: /(?<quote>['"])(.*?)\k<quote>/: Invalid group

Backtracking en Expresiones Regulares

¿Con que cadenas casa la expresión regular /^(11+)\1+$/?

> '1111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/) # 4 unos

[ '1111',

'11',

index: 0,

input: '1111' ]

> '111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/) # 3 unos

null

> '11111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/) # 5 unos

null

> '111111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/) # 6 unos

[ '111111',

'111',

index: 0,

input: '111111' ]

> '11111111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/) # 8 unos

[ '11111111',

'1111',

index: 0,

input: '11111111' ]

> '1111111'.match(/^(11+)\1+$/)

null

>

Diophantic Equations

A Diophantine equation is an indeterminate polynomial equation that allows the variables to be integers only.

On September 2009 I wrote a small piece in Perl Monks titled:

that illustrates (in Perl) how to solve a set of diophantine equations using Perl Extended Regular Expressions.

Exercise

Write a program that using a regular expression computes a integer solution to the diophantine equation \(4x+5y=77\)

Generalize the former solution and write a function:

diophantine(a, b, c)

that returns an array [x, y] containing a

solution to the diophantine equation

\(a \times x + b \times y = c\)

or null if there is no such solution

Since to solve this problem you have to dynamically create the regexp, review section Dynamically creating RegExp objects of the Eloquent JS book.

replace

The replace() method of the String objects returns a new string with some or all matches of

a pattern replaced by a replacement.

The pattern can be a string or a RegExp,

and the replacement can be a string or a function to be called

for each match.

> re = /apples/gi

/apples/gi

> str = "Apples are round, and apples are juicy."

'Apples are round, and apples are juicy.'

> newstr = str.replace(re, "oranges")

'oranges are round, and oranges are juicy.'

We can refer to matched groups in the replacement string:

console.log(

"Liskov, Barbara\nMcCarthy, John\nWadler, Philip"

.replace(/(\w+), (\w+)/g, "$2 $1"));

// → Barbara Liskov

// John McCarthy

// Philip Wadler

The $1 and $2 in the replacement string refer to the parenthesized groups in the pattern.

Using a function to compute the replacement string

The replacement string can be a function to be invoked to create the new substring (to put in place of the substring received):

let s = "the cia and fbi";

console.log(s.replace(/\b(fbi|cia)\b/g,

str => str.toUpperCase()));

// → the CIA and FBI

The arguments supplied to this function

(match, p1, p2, ..., pn, offset, string) => { ... }

are:

| Possible name | Supplied value |

|---|---|

| match | The matched substring. (Corresponds to $&.) |

p1, p2, … |

The nth parenthesized submatch string, provided the first argument to replace was a RegExp object. (Corresponds to $1, $2, etc.) For example, if /(\a+)(\b+)/, was given, p1 is the match for \a+, and p2 for \b+. |

offset |

The offset of the matched substring within the total string being examined (For example, if the total string was "abcd", and the matched substring was "bc", then this argument will be 1 |

| string | The total string being examined |

Ejemplo: Fahrenheit a Celsius

El siguiente ejemplo reemplaza los grados Fahrenheit con su equivalente en grados Celsius.

Los grados Fahrenheit deberían ser un número acabado en F.

La función devuelve el número Celsius acabado en C.

Por ejemplo, si el número de entrada es 212F, la función devuelve 100C. Si el número es 0F, la función devuelve -17.77777777777778C.

Véase solución en codepen.

[~/javascript/learning]$ pwd -P

/Users/casiano/local/src/javascript/learning

[~/javascript/learning]$ cat f2c.js

#!/usr/bin/env node

function f2c(x)

{

function convert(str, p1, offset, s)

{

return ((parseFloat(p1)-32) * 5/9) + "C";

}

var s = String(x);

var test = /(\d+(?:\.\d*)?)F\b/g;

return s.replace(test, convert);

}

var arg = process.argv[2] || "32F";

console.log(f2c(arg));

Ejecución:

[~/javascript/learning]$ ./f2c.js 100F

37.77777777777778C

[~/javascript/learning]$ ./f2c.js

0C

Greed and Lazy Operators

Exercise:

We have a text and need to replace all double quotes "..." with single quotes: '...

'. (We are not considering escaped double quotes inside)

What is the output for this regexp?:

let regexp = /".+"/g;

let str = 'a "witch" and her "broom" is one';

str.match(regexp);

See Greedy and lazy quantifiers at the Modern JavaScript book

Exercise:

Write a function that removes all comments from a piece of JavaScript code.

What is the output?

function stripComments(code) {

return code.replace(/\/\*[^]*\*\//g, "");

}

console.log(stripComments("1 + /* 2 */3"));

console.log(stripComments("1 /* a */+/* b */ 1"));

Lazy Quantifiers

The lazy mode of quantifiers is an opposite to the greedy mode. It means: repeat minimal number of times.

We can enable it by putting a question mark ? after the quantifier, so that it becomes *? or +? or even ?? for ?.

When a question mark ? is added after another quantifier it switches the matching mode from greedy to lazy.

Positive Lookahead

A positive lookahead has the syntax X(?=Y):

The regular expression engine finds X

and then matches only if there’s Y immediately after it and the search continues

inmediately after the X.

For more information, see section Lookahead and lookbehind of the Modern JavaScript Tutorial.

Example:

> x = "hello"

'hello'

> r = /l(?=o)/

/l(?=o)/

> z = r.exec(x)

[ 'l', index: 3, input: 'hello' ]

Exercise: What is the output?

> str = "1 turkey costs 30 €"

'1 turkey costs 30 €'

> str.match(/\d+(?=\s)(?=.*30)/)

Negative Lookahead

A negative lookahead has the syntax X(!=Y):

The regular expression engine finds X

and then matches only if there’s no Y immediately after the X and if so,

the search continues

inmediately after the X.

Exercise: What is the output? Whose of these twos is matched?

> reg = /\d+(?!€)(?!\$)/

/\d+(?!€)(?!\$)/

> s = '2€ is more than 2$ and 2+2 is 4'

'2€ is more than 2$ and 2+2 is 4'

> reg.exec(s)

Positive Lookbehind

Positive lookbehind has the syntax (?<=Y)X,

it matches X, but only if there’s Y before it.

> str = "1 turkey costs $30"

'1 turkey costs $30'

> str.match(/(?<=\$)\d+/)

[ '30', index: 16, input: '1 turkey costs $30', groups: undefined ]

Negative Lookbehind

Negative lookbehind has the syntax (?<!Y)X, it matches X,

but only if there’s no Y before it.

> str = 'I bought 2Kg of rice by 3€ at the Orotavas\' country market'

"I bought 2Kg of rice by 3€ at the Orotavas' country market"

> str.match(/(?<!t )\d+/)

[

'3',

index: 24,

input: "I bought 2Kg of rice by 3€ at the Orotavas' country market",

groups: undefined

]

Ejercicio: Poner Blanco después de Coma

Busque una solución al siguiente ejercicio (véase ’Regex to add space after punctuation sign’ en PerlMonks). Se quiere poner un espacio en blanco después de la aparición de cada coma:

> x = "a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f"

'a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f'

> x.replace(/,/g,", ")

'a, b, c, 1, 2, d, e, f'

pero se quiere que

- la sustitución no tenga lugar si la coma esta incrustada entre dos dígitos.

- Además se pide que si hay ya un espacio después de la coma, no se duplique.

- La siguiente solución logra el segundo objetivo, pero estropea los números:

> x = "a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f"

'a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f'

> x.replace(/,(\S)/g,", $1")

'a, b, c, 1, 2, d, e, f'

- Esta otra funciona bien con los números pero no con los espacios ya existentes:

> x = "a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f"

'a,b,c,1,2,d, e,f'

> x.replace(/,(\D)/g,", $1")

'a, b, c,1,2, d, e, f'

- Explique cuando casa esta expresión regular:

> r = /(\d[,.]\d)|(,(?=\S))/g

/(\d[,.]\d)|(,(?=\S))/g

- Aproveche que el método

replacepuede recibir como segundo argumento una función (vea replace):

> z = "a,b,1,2,d, 3,4,e"

'a,b,1,2,d, 3,4,e'

> r = /(\d[,.]\d)|(,(?=\S))/g

/(\d[,.]\d)|(,(?=\S))/g

> f = (_, p1, p2) => (p1 || p2 + " ")

[Function]

> z.replace(r, f)

'a, b, 1,2, d, 3,4, e'

Véase en codepen

search

- String.prototype.search

str.search(regexp)

If successful, search returns the index of the regular expression inside

the string. Otherwise, it returns -1.

When you want to know whether a pattern is found in a string use search

(similar to the regular expression test method); for more information

(but slower execution) use match (similar to the regular expression

exec method).

" word".search(/\S/)

// → 2

" ".search(/\S/)

// → -1

There is no way to indicate that the match should start at a given offset (like we can with the second argument to indexOf). However, you can do something as convolute like this!:

> z = " word"

' word'

> z.search(/(?<=^.{4})\S/ // search will match after offset 5

4

> z[4]

'r'

lastIndex

Regular expression objects have properties.

One such property is source, which contains the string that expression was created from.

Another property is lastIndex, which controls, in some limited circumstances, where the next match will start.

If your regular expression uses the g flag, you can use the exec

method multiple times to find successive matches in the same string.

When you do so, the search starts at the substring of str specified

by the regular expression’s lastIndex property.

> re = /d(b+)(d)/ig

/d(b+)(d)/gi

> z = "dBdxdbbdzdbd"

'dBdxdbbdzdbd'

> result = re.exec(z)

[ 'dBd', 'B', 'd', index: 0, input: 'dBdxdbbdzdbd' ]

> re.lastIndex

3

> result = re.exec(z)

[ 'dbbd', 'bb', 'd', index: 4, input: 'dBdxdbbdzdbd' ]

> re.lastIndex

8

> result = re.exec(z)

[ 'dbd', 'b', 'd', index: 9, input: 'dBdxdbbdzdbd' ]

> re.lastIndex

12

> z.length

12

> result = re.exec(z)

null

let input = "A string with 3 numbers in it... 42 and 88.";

let number = /\b\d+\b/g;

let match;

while (match = number.exec(input)) {

console.log("Found", match[0], "at", match.index);

}

// → Found 3 at 14

// Found 42 at 33

// Found 88 at 40

Otra Solución al Parsing de los Ficheros ini

Sticky flag “y”, searching at position

Regular expressions can have options, which are written after the closing slash.

- The

goption makes the expression global, which, among other things, causes thereplacemethod to replace all instances instead of just the first. - The

yoption makes it sticky, which means that it will not search ahead and skip part of the string when looking for a match.

The difference between the global and the sticky options is that, when sticky is enabled, the match will succeed only if it starts directly at lastIndex, whereas with global, it will search ahead for a position where a match can start.

let global = /abc/g;

console.log(global.exec("xyz abc"));

// → ["abc"]

let sticky = /abc/y;

console.log(sticky.exec("xyz abc"));

// → null

let str = 'let varName = "value"';

let regexp = /\w+/y;

regexp.lastIndex = 3;

console.log( regexp.exec(str) ); // null (there's a space at position 3, not a word)

regexp.lastIndex = 4;

console.log( regexp.exec(str) ); // varName (word at position 4)

Véase también:

Analizadores Léxicos usando la Sticky flag

Si combinamos la flag sticky con el uso de paréntesis con nombre podemos construir un analizador léxico.

Recuerda que la función de un analizador léxico es la de proporcionarnos un stream de tokens a partir de la cadena de entrada.

Por ejemplo, el tokenizer de espree funciona así:

> const espree = require('espree')

undefined

> espree.tokenize('var a = "hello"')

[

Token { type: 'Keyword', value: 'var', start: 0, end: 3 },

Token { type: 'Identifier', value: 'a', start: 4, end: 5 },

Token { type: 'Punctuator', value: '=', start: 6, end: 7 },

Token { type: 'String', value: '"hello"', start: 8, end: 15 }

]

Queremos hacer algo parecido.

Para ello usaremos el hecho de que podemos acceder al paréntesis que casa via el nombre:

> RE = /(?<NUM>\d+)|(?<ID>[a-z]+)|(?<OP>[-+*=])/y;

/(?<NUM>\d+)|(?<ID>[a-z]+)|(?<OP>[-+*=])/y

> input = 'x=2+b'

'x=2+b'

> while (m = RE.exec(input)) { console.log(m.groups) }

[Object: null prototype] { NUM: undefined, ID: 'x', OP: undefined }

[Object: null prototype] { NUM: undefined, ID: undefined, OP: '=' }

[Object: null prototype] { NUM: '2', ID: undefined, OP: undefined }

[Object: null prototype] { NUM: undefined, ID: undefined, OP: '+' }

[Object: null prototype] { NUM: undefined, ID: 'b', OP: undefined }

Puesto que la expresión regular es un OR excluyente, sólo una de las subexpresiones

casa y el resto está undefined.

Para detectar el token debemos recorrer el objeto buscando la clave cuyo valor no

está undefined:

> RE = /(?<NUM>\d+)|(?<ID>[a-z]+)|(?<OP>[-+*=])/y;

/(?<NUM>\d+)|(?<ID>[a-z]+)|(?<OP>[-+*=])/y

> input = 'x=2+b'

'x=2+b'

> names = ['NUM', 'ID', 'OP']

[ 'NUM', 'ID', 'OP' ]

> while (m = RE.exec(input)) {

console.log(names.find(n => m.groups[n] !== undefined)) }

ID

OP

NUM

OP

ID

El siguiente ejemplo ilustra la técnica:

[~/.../practicas/p2-t2-lexer(master)]$ cat sticky.js

const str = 'const varName = "value"';

console.log(str);

const SPACE = /(?<SPACE>\s+)/;

const RESERVEDWORD = /(?<RESERVEDWORD>\b(const|let)\b)/;

const ID = /(?<ID>([a-z_]\w+))/;

const STRING = /(?<STRING>"([^\\"]|\\.")*")/;

const OP = /(?<OP>[+*\/-=])/;

const tokens = [

['SPACE', SPACE], ['RESERVEDWORD', RESERVEDWORD], ['ID', ID],

['STRING', STRING], ['OP', OP]

];

const tokenNames = tokens.map(t => t[0]);

const tokenRegs = tokens.map(t => t[1]);

const buildOrRegexp = (regexps) => {

const sources = regexps.map(r => r.source);

const union = sources.join('|');

// console.log(union);

return new RegExp(union, 'y');

};

const regexp = buildOrRegexp(tokenRegs);

const getToken = (m) => tokenNames.find(tn => typeof m[tn] !== 'undefined');

let match;

while (match = regexp.exec(str)) {

//console.log(match.groups);

let t = getToken(match.groups);

console.log(`Found token '${t}' with value '${match.groups[t]}'`);

}

See also:

- Example: using sticky matching for tokenizing inside the chapter New regular expression features in ECMAScript 6

Parsing Ficheros ini

- Parsing an INI file Eloquent JavaScript

Ejercicios

- Ejercicios de Expresiones Regulares en los apuntes

- Ejercicio: Palabras repetidas Vídeo del profesor

- Ejercicio: Buscar las secuencias que empiezan por 12 en posiciones múltiplos de 6 Vídeo del profesor

- Tarea. Haga los ejercicios en https://regexone.com/

- Tarea. Haga los ejercicios en https://www.w3resource.com/javascript-exercises/javascript-regexp-exercises.php

Práctica p3-t2-regexp

Resuelva los ejercicios de Expresiones Regulares propuestos por el profesor

Unicode, UTF-16 and JavaScript

The Unicode Standard

The way JavaScript models Strings is based on the Unicode standard.

This standard assigns a number called code point to virtually every character you would ever need, including characters from Greek, Arabic, Japanese, Armenian, and so on. If we have a number for every character, a string can be described by a sequence of numbers.

One advantage of Unicode over other possible sets is that

- The first 256 code points are identical to ISO-8859-1, and hence also ASCII.

- In addition, the vast majority of commonly used characters are representable by only two bytes, in a region called the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP).

Planes

In the Unicode standard, a plane is a continuous group of 65,536 (\(2^{16}\)) code points. The Unicode code space is divided into seventeen planes.

The BMP is the first (code points from U+0000 to U+FFFF), the other 16 planes are called astral planes. Worth noting that planes 3 to 13 are currently empty.

The code points contained in astral planes are called astral code points.

Astral code points go from U+10000 to U+10FFFF.

JavaScript’s representation uses 16 bits per string element, which can describe up to \(2^{16}\) different characters. But Unicode defines more characters than that: about twice as many. So some characters, such as many emoji, take up two character positions in JavaScript strings.

When comparing strings, JavaScript goes over the characters from left to right, comparing the Unicode codes one by one.

Private Use Areas (PUA)

In Unicode, a Private Use Area (PUA) is a range of code points that, by definition, will not be assigned characters by the Unicode Consortium.

Three private use areas are defined: one in the Basic Multilingual Plane (U+E000–U+F8FF), and one each in, and nearly covering, planes 15 and 16 (U+F0000–U+FFFFD, U+100000–U+10FFFD).

The code points in these areas cannot be considered as standardized characters in Unicode itself. They are intentionally left undefined so that third parties may define their own characters without conflicting with Unicode Consortium assignments. The Private Use Areas will remain allocated for that purpose in all future Unicode versions.

UTF-16

JavaScript strings are encoded as a sequence of 16-bit numbers. These are called code units.

A Unicode character code was initially supposed to fit within such a unit (which gives you a little over 65,000 characters). When it became clear that wasn’t going to be enough, many people balked at the need to use more memory per character.

To address these concerns, UTF-16 (UCS Transformation Format for 16 Planes of Group 00), the format used by JavaScript strings, was invented. It describes most common characters using a single 16-bit code unit but uses a pair of two such units for others.

JS and UTF-16 and Problems Processing Strings

Some people think UTF-16 is a bad idea: It’s easy to write programs that pretend code units and characters are the same thing.

If your language doesn’t use two-unit characters, that will appear to work just fine. But as soon as someone tries to use such a program with some less common characters, it breaks. Fortunately, with the advent of emoji, everybody has started using two-unit characters, and the burden of dealing with such problems is more fairly distributed.

Unfortunately, obvious operations on JavaScript strings, such as getting their length through the length property and accessing their content using square brackets, deal only with code units.

// Two emoji characters, horse and shoe

let horseShoe = "🐴👟";

console.log("horseShoe.length ="+horseShoe.length);

// → 4 four code units but two code points

You can use the spread operator (...) to turn strings into arrays

and compute the length of the string and access the character at

a given position:

console.log("[...'abc'] = "+inspect([...'abc'])); // [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ]

console.log("[...'🐴👟'].length = "+[...'🐴👟'].length);

// → 2

console.log(horseShoe[0]);

// → (Invalid half-character)

console.log([...horseShoe][0]);

// 🐴

See this code at repo ULL-ESIT-PL/unicode-js.

Another example is reversing a string. Let us define the reversefunction like this:

> reverse = str => str.split('').reverse().join('')

[Function: reverse]

It seems to work:

> reverse('mañana')

'anañam'

However, it messes up strings that contain combining marks or astral symbols:

> reverse('💩🍎')

'�🂩�'

To reverse astral symbols correctly we can use again the spread operator:

> reverse = str => [...str].reverse().join('')

[Function: reverse]

> reverse('💩🍎')

'🍎💩'

JavaScript’s charCodeAt method gives you a code unit, not a full character code. The codePointAt method, added later, does give a full Unicode character.

So we could use that to get characters from a string.

But the argument passed to codePointAt is still an index into the sequence of code units.

So to run over all characters in a string, we’d still need to deal with the question of whether a character takes up one or two code units.

A for/of loop can be used to iterate on strings.

for (let ch of "🐴👟") {

console.log(ch + " has " + ch.length + " units"); // 2 units

}

Like codePointAt, this type of loop was introduced at a time where people were acutely aware of the problems with UTF-16. When you use it to loop over a string, it gives you real characters, not code units.

[~/.../clases/20200325-miercoles(master)]$ cat stringTraversing.js

const len = (x) => [...x].length;

String.prototype.char = function(i) { return [...this][i]; }

let str = "🌹🐉";

for (let i=0; i<len(str); i++) {

console.log(

`${str.codePointAt(i)} (${str.charCodeAt(2*i)}, ${str.charCodeAt(2*i+1)}) => ${str.char(i)}`

);

}

Execution:

[~/.../clases/20200325-miercoles(master)]$ node stringTraversing.js

127801 (55356, 57145) => 🌹

57145 (55357, 56329) => 🐉

If you have a character (which will be a string of one or two code units), you can use codePointAt() to get its code point and charCodeAt to get its code unit.

let horseShoe = "🐴👟";

console.log("ABC".charCodeAt(0)); // returns 65

console.log("ABC".charCodeAt(1)); // returns 66

console.log(horseShoe.charCodeAt(0));

// → 55357 (Code of the half-character)

console.log(horseShoe.charCodeAt(1));

// → 56372

console.log(horseShoe.charCodeAt(2));

// → 55357

console.log(horseShoe.charCodeAt(3));

// → 56415

console.log(horseShoe.codePointAt(0));

// → 128052 (Actual code for horse emoji)

console.log(horseShoe.codePointAt(2));

// → 128095 (Actual code for shoe emoji)

console.log(String.fromCharCode(55357, 56372, 55357, 56415)); // → 🐴👟

- Examples of JavaScript y Unicode (Repo en GitHub unicode-js)

Checking if a Codepoint is in the Basic Multilingual Plane BMP

A natural question seems to be:

How to know if a codepoint is inside the BMP or is astral?

Did you realize in the former examples that all the first code units of all emojis were quite large?. They were larger than 55295?

The following code seems to work. The last BMP Character seems to be 0xD7FF (55295):

[~/.../clases/20200325-miercoles(master)]$ cat is-bmp.js

const isInRange = (str) => /[\u0000-\ud7ff]/u.test(str);

const isISO8859 = char => char.charCodeAt(0) < 255;

const isBMP = char => char.charCodeAt(0) <= 0xD7FF;

const checkIf = (condition, char) => {

console.log(

`${char} with codePoint ${char.codePointAt(0)}`

+ ` and charCodeAt(0) ${char.charCodeAt(0)}`

+ ` ${condition.name}(${char})=${condition(char)}`

+ ` isInRange=${isInRange(char)}`);

};

console.log("-----ISO8859-----")

checkIf(isISO8859,"A"); // true

checkIf(isISO8859,"ñ"); // true

checkIf(isISO8859,"α"); // false

checkIf(isISO8859,"п"); // false

checkIf(isISO8859,"👟"); // false

console.log("-----BMP-----")

checkIf(isBMP,"A"); // true

checkIf(isBMP,"ñ"); // true

checkIf(isBMP,"α"); // true

checkIf(isBMP,"п"); // true

checkIf(isBMP,"𨭎"); // false

checkIf(isBMP,"👟"); // false

checkIf(isBMP,"🐴"); // false

checkIf(isBMP,"😂"); // false

checkIf(isBMP,'﷽ '); // The longest single character I ever seen!!

Execution:

[~/.../clases/20200325-miercoles(master)]$ node is-bmp.js

-----ISO8859-----

A with codePoint 65 and charCodeAt(0) 65 isISO8859(A)=true isInRange=true

ñ with codePoint 241 and charCodeAt(0) 241 isISO8859(ñ)=true isInRange=true

α with codePoint 945 and charCodeAt(0) 945 isISO8859(α)=false isInRange=true

п with codePoint 1087 and charCodeAt(0) 1087 isISO8859(п)=false isInRange=true

👟 with codePoint 128095 and charCodeAt(0) 55357 isISO8859(👟)=false isInRange=false

-----BMP-----

A with codePoint 65 and charCodeAt(0) 65 isBMP(A)=true isInRange=true

ñ with codePoint 241 and charCodeAt(0) 241 isBMP(ñ)=true isInRange=true

α with codePoint 945 and charCodeAt(0) 945 isBMP(α)=true isInRange=true

п with codePoint 1087 and charCodeAt(0) 1087 isBMP(п)=true isInRange=true

𨭎 with codePoint 166734 and charCodeAt(0) 55394 isBMP(𨭎)=false isInRange=false

👟 with codePoint 128095 and charCodeAt(0) 55357 isBMP(👟)=false isInRange=false

🐴 with codePoint 128052 and charCodeAt(0) 55357 isBMP(🐴)=false isInRange=false

😂 with codePoint 128514 and charCodeAt(0) 55357 isBMP(😂)=false isInRange=false

﷽ with codePoint 65021 and charCodeAt(0) 65021 isBMP(﷽ )=false isInRange=true

See BMP en la Wikipedia.

See also this page in Unicode.org to see the properties of a given unicode character. Among the if the codepoint belongs to the BMP.

Unicode and Editors

- Visual Studio Code Extension: Insert Unicode

- En Vim:

gashows the decimal, hexadecimal and octal value of the character under the cursor.- Any utf character at all can be entered with a

Ctrl-Vprefix, either<Ctrl-V> u aaaaor<Ctrl-V> U bbbbbbbb, with0 <= aaaa <= FFFF, or0 <= bbbbbbbb <= 7FFFFFFF. - Digraphs work by pressing CTRL-K and a two-letter combination while in insert mode.

<Ctrl-K> a *producesα<Ctrl-K> b *producesβ,<Ctrl-k> d =producesд, etc.

Unicode: Regular Expressions and International characters

EloquentJS: International characters

Because of JavaScript’s initial simplistic implementation and the fact that this simplistic approach was later set in stone as standard behavior, JavaScript’s regular expressions are rather dumb about characters that do not appear in the English language. For example, as far as JavaScript’s regular expressions are concerned, a word character is only one of the 26 characters in the Latin alphabet (uppercase or lowercase), decimal digits, and, for some reason, the underscore character. Things like é or β, which most definitely are word characters, will not match \w (and will match uppercase \W, the nonword category).

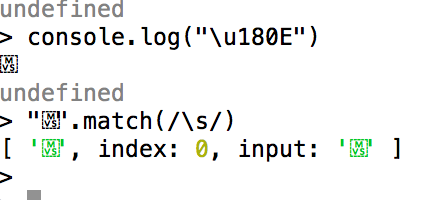

\s: Strange behaviors

By a strange historical accident, \s (whitespace) does not have this problem and matches all characters that the Unicode standard

considers whitespace, including things like the nonbreaking space

and the Mongolian vowel separator:

Option \u

By default, regular expressions work on code units:

See this example in this repo ULL-ESIT-PL/unicode-js

[~/.../src/unicode-js(master)]$ cat apple-regexp-test.js

console.log(/🍎{3}/.test("🍎🍎🍎"));

// → false

console.log(/🍎{3}/u.test("🍎🍎🍎"));

// → true

console.log(/<.>/.test("<🌹>"));

// → false

console.log(/<.>/u.test("<🌹>"));

// → true

The problem is that the code point 🍎 in the first line

is treated as two code units,

and the /🍎{3}/ part is interpreted as 3 repetitions of the second code unit.

Similarly, the dot matches a single code unit, not the two that make up the rose emoji.

You must add a u option (for Unicode) to your regular expression to make it treat such characters properly. The wrong behavior remains the default, unfortunately, because changing that might cause problems for existing code that depends on it.

\u inside a string allow us to introduce unicode characters using

\u#codepoint:

> console.log("\u03A0")

Π

> console.log("\u03B1")

α

> "Πα".match(/\u03A0(\u03B1)/u)

[ 'Πα', 'α', index: 0, input: 'Πα' ]

\p macro: properties

Every character in Unicode has a lot of properties. They describe what category the character belongs to, contain miscellaneous information about it.

For instance, if a character has Letter property, it means that the character belongs to an alphabet (of any language).

And Number property means that it’s a digit: maybe Arabic or Chinese, and so on.

The \p macro can be used in any regular expression using the /u option to match the characters to which the Unicode standard assigns the specified Unicode property.

For instance, \p{Letter} denotes a letter in any of language. We can also use \p{L}, as L is an alias of Letter.

There are shorter aliases for almost every property.

ost of the Unicode characters are associated with a specific script. The standard contains 140 different scripts — 81 are still in use today, and 59 are historic.

People are writing texts in at least 80 other writing systems, many of which We wouldn’t even recognize. For example, here’s a sample of Tamil handwriting:

For example:

[~/.../src/unicode-js(master)]$ cat property.js

console.log(/\p{Script=Greek}/u.test("α"));

// → true

console.log(/\p{Script=Arabic}/u.test("α"));

// → false

console.log(/\p{Alphabetic}/u.test("α"));

// → true

console.log(/\p{Alphabetic}/u.test("!"));

// → false

console.log(/\p{Number}/u.test("६६७"));

// → true

Here is a regexp that matches identifiers:

> "\u216B"

'Ⅻ'

> id = /[\p{L}_][\p{L}\p{N}_]*/ug

/[\p{L}_][\p{L}\p{N}_]*/gu

> 'Русский६ 45 ; ab2 ... αβ६६७ -- __ b\u216B'.match(id)

[ 'Русский६', 'ab2', 'αβ६६७', '__', 'bⅫ' ]

Unicode supports many different properties, their full list would require more space than we have here. For more, see this references:

- Properties by a character: https://unicode.org/cldr/utility/character.jsp.

- Characters by a property: https://unicode.org/cldr/utility/list-unicodeset.jsp.

- Short aliases for properties: https://www.unicode.org/Public/UCD/latest/ucd/PropertyValueAliases.txt.

- A full base of Unicode characters in text format, with all properties: https://www.unicode.org/Public/UCD/latest/ucd/.

Read Also

- Unicode.org

- See section Unicode properties \p{…} of the Modern Javascript book for a list of properties and more examples about

\p - JavaScript has a Unicode problem 2013

- Eloquent JS: International characters

XRegExp: Expresiones Regulares Extendidas (a la Perl)

API de XRegExp

- XRegExp

- XRegExp.addToken

- XRegExp.build (addon)

- XRegExp.cache

- XRegExp.escape

- XRegExp.exec

- XRegExp.forEach

- XRegExp.globalize

- XRegExp.install

- XRegExp.isInstalled

- XRegExp.isRegExp

- XRegExp.match

- XRegExp.matchChain

- XRegExp.matchRecursive (addon)

- XRegExp.replace

- XRegExp.replaceEach

- XRegExp.split

- XRegExp.test

- XRegExp.uninstall

- XRegExp.union

- XRegExp.version

XRegExp instance properties

- [

.xregexp.source](http://xregexp.com/api/#dot-source) (The original pattern provided to the XRegExp constructor) - [

.xregexp.flags](http://xregexp.com/api/#dot-flags) (The original flags provided to the XRegExp constructor)

XRegExp. Unicode

Módulo @ull-esit-pl/uninums

Javascript supports Unicode strings, but parsing such strings to numbers is unsupported (e.g., the user enters a phone number using Chinese numerals).

uninums.js is a small utility script that implements five methods for handling non-ASCII numerals in Javascript

> uninums = require("@ull-esit-pl/uninums")

{ normalSpaces: [Function: normalSpaces],

normalDigits: [Function: normalDigits],

parseUniInt: [Function: parseUniInt],

parseUniFloat: [Function: parseUniFloat],

sortNumeric: [Function: sortNumeric] }

> uninums.parseUniInt('६.६')

6

> uninums.parseUniFloat('६.६')

6.6

> uninums.parseUniFloat('६.६e६')

6600000

> uninums.sortNumeric(['٣ dogs','١٠ cats','٢ mice'])

[ '٢ mice', '٣ dogs', '١٠ cats' ]

> uninums.normalDigits('٢ mice')

'2 mice'

> uninums.normalDigits('٣ dog')

'3 dog'

> uninums.normalDigits('١٠ cats')

'10 cats'

> uninums.normalDigits('٠۴६')

'046'

Extensiones a las Expresiones Regulares en ECMA6

RegExps en Otros lenguajes

Antiguos apuntes del profesor sobre el uso de RegExp en otros lenguajes:

Perl

Varios Lenguajes

Python

Ruby

C

sed

Análisis Léxico

- Ejemplo de Analizador Léxico para JS

- Descripción de la Práctica: Analizador Léxico para Un Subconjunto de JavaScript gitbooks.io

- Compiler Construction by Wikipedians. Chapter Lexical Analysis

- Un caso a estudiar: El módulo npm lexical-parser

- Esprima. Chapter 3. Lexical Analysis (Tokenization)

- jison-lex

- lexer

- Expresiones Regulares en Flex

Práctica p9-t2-lexer

Práctica p9-t2-lexer-with-server

Referencias

- Apuntes de Expresiones Regulares del profesor

- Eloquent JavaScript: Regular Expressions

- Chapter Regular expressions in the “Modern JavaScript Tutorial” book

- New regular expression features in ECMAScript 6

Otros Apuntes del Profesor

- Apuntes 16/17 de Expresiones Regulares del profesor (gitbook)

- Expresiones Regulares y Análisis Léxico en JavaScript Apuntes del profesor cursos 2012-2014. Latex2html, LateX, GitHub

- Apuntes de la Asignatura Procesadores de Lenguajes GitHub Cursos 13-15 http://crguezl.github.io/pl-html

- Expresiones Regulares y Análisis Léxico en JavaScript Latex2Html, LaTeX, nereida